Understanding Cortisol and Stress in Dogs

Date: November 18, 2023 Author: Roberto Barata How to cite: Barata, R. (2023). Understanding Cortisol and Stress in Dogs, A Review. Human-Animal Science. Cortisol, often called the “stress hormone,” is vital in managing stress in humans and animals, influencing biological and psychological functions. Produced in the adrenal glands, it is integral to various bodily processes, including metabolism, immune response, and memory formation. Its presence, although constant, varies throughout the day, peaking in the morning and gradually declining by evening. These fluctuations are essential for maintaining health and homeostasis, making cortisol a critical focus in human and veterinary medicine and animal behavior studies. Physiological Factors: Stress: Both physical and psychological stress are primary triggers for increased cortisol production. Sleep Patterns: Disruptions in sleep or irregular sleep patterns can affect cortisol levels. Diet and Nutrition: Certain dietary patterns, such as high sugar or lack of certain nutrients, can influence cortisol. Exercise: Physical activity impacts cortisol, with intense exercise typically increasing its levels. Illness or Injury: The body’s response to illness or injury often involves a rise in cortisol. Hormonal Fluctuations: Changes in other hormones, like estrogen and testosterone, can affect cortisol levels. Pregnancy: Cortisol levels naturally change during pregnancy. Age: Cortisol levels can vary, often increasing as individuals age. Breed and Genetics: Breed-specific traits and genetics can influence how cortisol is regulated in pets. Psychological Factors: Emotional Stress: Anxiety, depression, and other emotional states can lead to elevated cortisol levels. Mental Health Disorders: Conditions like PTSD, anxiety disorders, and depression are often linked with altered cortisol levels. Coping Strategies: How individuals cope with stress can impact their cortisol levels. Personality Traits: Certain personality traits, such as a tendency towards anxiety or hostility, can influence cortisol production. Environmental Factors: Exposure to Light: Exposure to artificial light, mainly blue light in the evening, can disrupt cortisol rhythms. Temperature and Climate: Extreme temperatures and climate conditions can impact cortisol levels. Altitude: Higher altitudes have been shown to affect cortisol. Seasonal Changes: Seasonal variations, like those in daylight and temperature, can influence cortisol patterns. Social and Lifestyle Factors: Social Interactions: Both positive and negative social interactions can influence cortisol levels. Human Interaction: The quality and nature of human-animal interactions, including training and handling, can affect cortisol levels in pets. Life Events: Major life events, whether positive or negative, can change cortisol levels. Medical and Pharmacological Factors: Medications: Certain medications, like corticosteroids, can directly influence cortisol levels. Medical Conditions: Conditions like Cushing’s syndrome or Addison’s disease directly affect cortisol production. Surgical Procedures: Surgical stress can lead to a temporary increase in cortisol levels. In animals, it prepares the body for fight-or-flight responses and modulates long-term processes like metabolism and immune responses. However, cortisol’s impact extends beyond acute stress scenarios, influencing how animals adapt to their environments and cope with stressors. This variability is influenced by genetics, environment, and past experiences. For example, dog breeds may exhibit varying cortisol responses due to genetic predispositions. Similarly, an individual dog’s experiences, like past trauma, can shape its cortisol response, manifesting in behaviors indicative of anxiety or stress. In cats, stress-related behavioral changes often manifest subtly, necessitating keen observation from owners for effective management. The enhancement of learning is a positive aspect of cortisol, similar to its increased levels during courtship, mating, and efforts to obtain food. While cortisol’s production in response to perceived threats, pain, or challenging environmental interactions is adaptive and beneficial, prolonged exposure to these stressors is inherently harmful. It can lead to adverse effects of cortisol. Given its role in advantageous and disadvantageous circumstances, viewing cortisol as invariably detrimental is incorrect. An individual’s welfare is determined by its ability to cope with its environment, with states ranging from excellent to poor. Welfare is compromised by difficulty or failure in coping. Coping strategies involve behavioral, physiological, and immunological responses coordinated by the brain. Emotions like pain, fear, and pleasure are often integral to these strategies and are crucial to understanding welfare. Good health is essential for positive welfare and is closely linked with coping with stress. Stress invariably indicates poor welfare, but temporary poor welfare may not always be due to stress (Broom & Johnson, 1993). Certain environmental conditions, like inadequate housing, may not trigger a change in cortisol levels. Therefore, the absence of increased cortisol does not necessarily mean an animal is free of problems. Often, chronic issues prompt coping mechanisms that do not involve cortisol, leading to other adverse outcomes. Thus, various welfare indicators are necessary to detect problems in humans and non-humans. Brain damage can indicate poor welfare, especially in the hippocampus and related areas. Such damage may result from factors like high-fat diets, alcohol consumption, food restriction, or sleep deprivation, all without affecting cortisol levels. Abnormal behaviors, including stereotypies or heightened aggression, can also signal poor welfare in cases where cortisol levels remain unchanged. Cortisol fluctuations do not always indicate poor welfare; they may be natural responses to courtship or active food searching. Therefore, understanding the context of cortisol changes is crucial for accurately interpreting physiological data related to welfare. Acute and Chronic Stress in Animals As commonly understood, stress refers to environmental influences that overwhelm an individual’s control systems, leading to negative outcomes and possibly diminished overall well-being (Broom & Johnson, 1993; Broom, 2014). This interpretation suggests that all stress is harmful, proposing that what is often termed ‘good stress’ should be classified as stimulation instead. Certain challenging situations can provide beneficial experiences during development, but these should not be categorized as stress. This concept aligns with Lazarus’s (2006) view that stress occurs when demands are perceived to exceed personal capabilities. However, a more functional definition that applies universally to all animals, irrespective of perception, is favored. Stress is an inevitable aspect of life, crucial for survival, and manifests in two primary forms: acute and chronic stress. These stress types are vital for wild animals and domesticated pets like dogs and cats. Acute stress, an immediate response to perceived threats, is exemplified by a deer’s fight-or-flight reaction upon sensing a predator. This response involves a hormonal surge, including cortisol, leading to heightened alertness and readiness for action. In domestic animals, acute

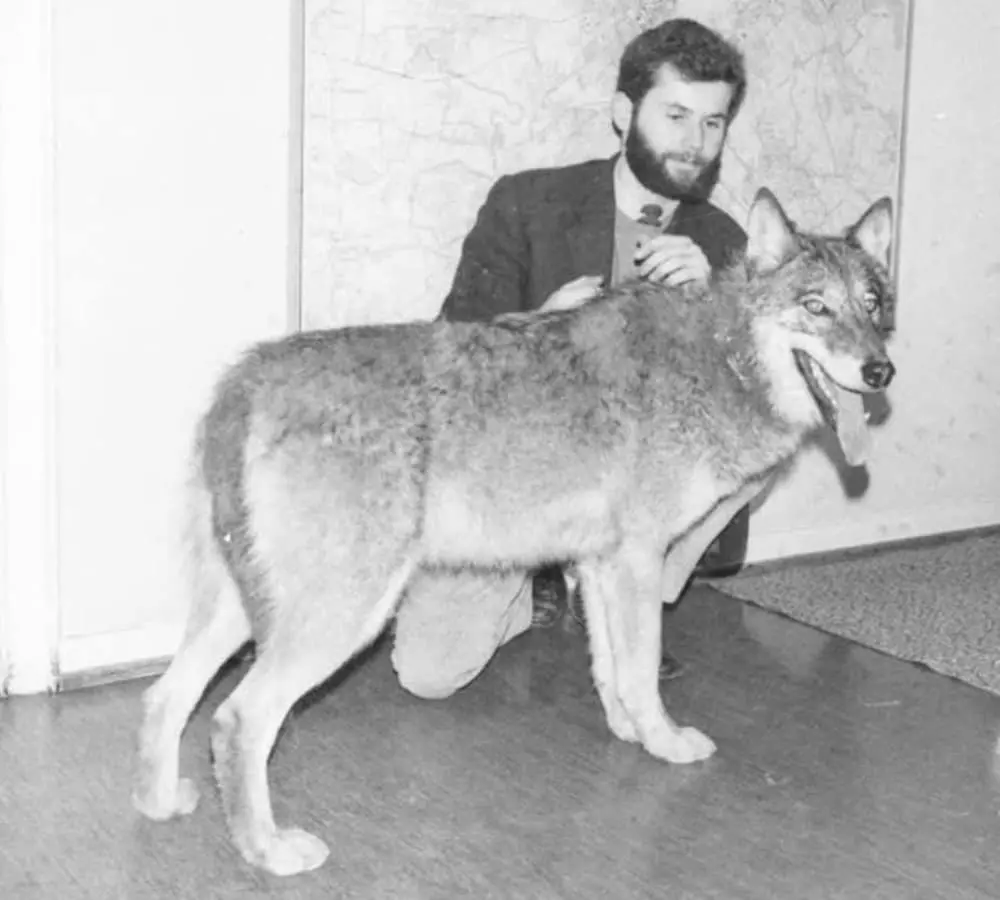

Zimen’s Wolf-Dog Experiment

Human-Animal Science

Ritualized Behavior

Human-Animal Science

The Efficacy and Misconceptions of the “Time-out” Procedure in Dog Training

Human-Animal Science

Optimism and Pessimism in Non-Human Species

Human-Animal Science

Dogs and Sleep: The Forgotten and Underestimated Need

Human-Animal Science

Why Don’t They Say “Goodbye”?

Human-Animal Science

Coping in Animal Behavior

Human-Animal Science

Aggressive and Fearful Behavior in Dogs: Understanding the Misunderstandings

Human-Animal Science

The Silent Suffering of Horses and the (In)human(e) Paradox

Human-Animal Science